No matter what the size or scope, every project in which you choose to participate should follow some type of planned workflow. Whether it's for print, film, video, or Web delivery (or all four!), you should establish a process to guide the production of your presentation.

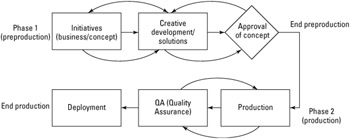

Before we can explore the way in which Flash fits into a Web production workflow, we need to define a holistic approach to Web production in general. Figure 3-1 shows a typical example of the Web production process within an Internet production company.

| Note |

The phases of production have been coined differently by various project managers and companies. Some interactive agencies refer to preproduction as an "architecture phase" or a "planning phase." |

As a Web developer or member of a creative team, you will be approached by companies (or representatives for other departments) to help solve problems with projects. A problem may or may not be well defined by the parties coming to you. The goal of Phase I is to thoroughly define the problem, offer solutions for the problem, and approve one or more solutions for final production.

Before you can help someone solve a problem, you need to determine what the problem is and whether there is more than one problem. When we say problem, we don't mean something that's necessarily troublesome or irritating. Think of it more as a math problem, where you know what you want — you're just not sure how to get there. When you're attempting to define a client's problem, start by asking them the following questions:

What's the message you want to deliver? Is it a product that you want to feature on an existing Web site?

Who's your current audience?

Who's your ideal audience? (Don't let them say, "Everyone!")

What branding materials (logos, colors, and identity) do you already have in place?

Who are your competitors? What do you know about your competitors?

The next to last question points to a bigger picture, one in which the client may already have several emotive keywords that define their brand. Try to define the emotional heart and feeling of their message — get them to be descriptive. Don't leave the meeting with the words edgy or sexy as the only descriptive terms for the message.

| Tip |

Never go into a meeting or a planning session without a white board or a big pad of paper. Documenting everyone's ideas and letting the group see the discussion in a visual format is always a good idea. If all participants are willing, it's often useful to record the meeting with a digital voice recorder or video camera, so that it can be reviewed outside of the meeting. There are also new products on the market that enable you to record every detail of a meeting, such as Macromedia Breeze Live, which enables you to conduct live meetings, as well as record them, over the Internet. Robert often uses his Tablet PC with Microsoft OneNote to record live audio that's synchronized with his notes from the meeting. You can find more information about Macromedia Breeze Live at www.macromedia.com/breeze. |

You can also start to ask the following technical questions at this point:

What type of browser support do you want to have?

Do you have an idea of a Web technology (Shockwave; Flash; Dynamic HyperText Markup Language, or DHTML; Scalable Vector Graphics, or SVG) that you want to use?

Does the message need to be delivered in a Web browser? Can it be in a downloadable application such as a stand-alone player? A CD-ROM? A DVD?

What type of computer processing speed should be supported? What other types of hardware concerns might exist (for example, hi-fi audio)?

Of course, many clients and company reps look to you for the technical answers. If this is the case, the most important questions are

Who's your audience?

Who do you want to be your audience?

Your audience determines, in many ways, what type of technology to choose for the presentation. If the client says that Ma and Pa from a country farm should be able to view the Web site with no hassle, then you may need to consider a non-Flash presentation (such as HTML 3.0 or earlier), unless it's packaged as a stand-alone player that's installed with a CD-ROM (provided to Ma and Pa by the client). However, if they say that their ideal audience is someone who has a 56K modem and likes to watch cartoons, then you're getting closer to a Flash-based presentation. If the client has any demographic information for their user base, ask for it up front. Putting on a show for a crowd is difficult if you don't know who's in the crowd.

The client or company reps come to you for a reason — they want to walk away with a completed and successful project. As you initially discuss the message and audience for the presentation, you also need to get a clear picture of what the client expects to get from you.

Will you be producing just one piece of a larger production?

Do they need you to host the Web site? Or do they already have a Web server and a staff to support it?

Do they need you to maintain the Web site after handoff?

Do they expect you to market the presentation? If not, what resources are in place to advertise the message?

When does the client expect you to deliver proposals, concepts, and the finished piece? These important dates are often referred to as milestones. The payment schedule for a project is often linked to production milestones.

Will they expect to receive copies of all the files you produce, including your source .fla files?

What are the costs associated with developing a proposal? Will you do work on speculation of a potential project? Or will you be paid for your time to develop a concept pitch? (You should determine this before you walk into your initial meeting with the client.) Of course, if you're working with a production team in a company, you're already being paid a salary to provide a role within the company.

At this point, you'll want to plan the next meeting with your client or company reps. Give them a realistic time frame for coming back to them with your ideas. This amount of time will vary from project to project and will depend on your level of expertise with the materials involved with the presentation.

After you leave the meeting, you'll go back to your design studio and start cranking out materials, right? Yes and no. Give yourself plenty of time to work with the client's materials (what you gathered from the initial meeting). If your client sells shoes, read up on the shoe business. See what the client's competitors are doing to promote their message — visit their Web sites, go to stores and compare the products, and read any consumer reports that you can find about your client's products or services. You should have a clear understanding of your client's market and a clear picture of how your client distinguishes their company or their product from their competitors'.

After you (and other members of your creative team) have completed a round of research, sit down and discuss the findings. Start defining the project in terms of mood, response, and time. Is this a serious message? Do you want the viewer to laugh? How quickly should this presentation happen? Sketch out any ideas you and any other member of the team may have. Create a chart that lists the emotional keywords for your presentation.

At a certain point, you need to start developing some visual material that articulates the message to the audience. Of course, your initial audience will be the client. You are preparing materials for them, not the consumer audience. We assume here that you are creating a Flash-based Web site for your client. For any interactive presentation, you need to prepare the following:

An organizational flowchart for the site

A process flowchart for the experience

A functional specification for the interface

A prototype or a series of comps

| Tip |

You can use tools such as Microsoft Visio (www.microsoft.com/visio) or Omni Group's OmniGraffle for Mac (www.omnigroup.com/applications/omnigraffle). For more information on the Visio 2003 Bible, published by Wiley, go to www.flashsupport.com/books/visio. |

An organizational flowchart is a simple document that describes the scope of a site or presentation. Other names for this type of chart are site chart, navigation flowchart, and layout flowchart. It includes the major sections of the presentation. For example, if you're creating a Flash movie for a portfolio site, you might have a main menu and four content areas: About, Portfolio, Resumé, and Contact. In an organizational flowchart, this would look like Figure 3-2.

A process flowchart constructs the interactive experience of the presentation and shows the decision-making process involved for each area of the site. There are a few types of process charts. A basic process flowchart displays the decisions an end-user will make. For example, what type of options does a user have on any given page of the site? Another type of flowchart shows the programming logic involved for the end-user process chart. For example, will certain conditions need to exist before a user can enter a certain area of the site? Does he have to pass a test, finish a section of a game, or enter a username and password? Refer to Figure 3-3 for a preliminary flowchart for a section of our portfolio Web site. We discuss the actual symbols of the flowchart later in this chapter.

A functional specification (see Figure 3-4) is a document that breaks down the elements for each step in the organizational and/or process flowchart. This is by far the most important piece of documentation that you can create for yourself and your team. Each page of a functional specification (functional spec, for short) lists all the assets used on a page (or Flash keyframe, Movie Clip) and indicates the following information for each asset:

Item ID: This is part of the naming convention for your files and assets. It should be part of the filename, or Flash symbol and instance name. It should also be used in organizational and process flowcharts.

Type: This part of the spec defines the name you're assigning to the asset, in more natural language, such as Home Button.

Purpose: You should be able to clearly explain why this element is part of the presentation. If you can't, then you should consider omitting it from the project.

Format: This column indicates what technology (or what component of the technology) will be utilized to accomplish the needs of the asset. In an all-Flash presentation, list the symbol type or timeline element (frames, scene, nested Movie Clips) necessary to accomplish the goals of the asset.

|

Project: |

Flash interface v2.0 |

Section: |

1 of 5 (Main Menu) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No. |

Type |

Purpose |

Content |

Format |

|

1.A |

Navigation bar |

To provide easier access to site content. |

A menu bar that is fixed at the top edge of the browser window. |

|

|

1.A.1 |

Directory buttons |

To provide a means of accessing any of the portfolio sections. |

Names each content area. For example: audio, video, graphics, etc. |

Horizontal menu list or ComboBox component (skinned). |

|

1.A.2 |

Home button |

Allows user to always get back to the opening page |

The text:ìhomeî. |

Button component (skinned). |

|

1.A.3 |

Search field |

To provide a means of entering a specific word or prhase to search site contents. |

A white text search field with the word ìsearchî |

Flash dynamic text field. |

|

1.A.4 |

Sign up |

Captuers the users email address for a site mailing list. |

Text field(s) to enter name and e-mail address. |

Button component generating a pop-up. Sign up using ColdFusion. |

|

1.A.5 |

Back button |

Allows the user to see the last page viewed without losing menu items |

The text ìback.î |

Button component (skinned). |

|

1.A.6 |

Logo or ID |

Proives a means of personal branding. |

A spider web, with text of the website name in Arial Narrow. |

Graphics in Freehand and Flash. |

| Note |

Functional specs come in all shapes and sizes. Each company usually has their own template or approach to constructing a functional spec. The client should always approve the functional spec, so that you and your client have an agreement about the scope of the project. |

Finally, after you have a plan for your project, you'll want to start creating some graphics to provide an atmosphere for the client presentation. Gather placement graphics (company logos, typefaces, photographs) or appropriate "temporary" resources for purposes of illustration. Construct one composition, or comp, that represents each major section or theme of the site. In our portfolio content site example, you might create a comp for the main page and a comp for one of the portfolio work sections, such as "Animation." Don't create a comp for each page of the portfolio section. You simply want to establish the feel for the content you will create for the client. We recommend that you use the tool(s) with which you feel most comfortable creating content. If you're better at using FreeHand or Photoshop to create layouts, then use that application. If you're comfortable with Flash for assembling content, then use it.

| Caution |

Do not use copyrighted material for final production use, unless you have secured the appropriate rights to use the material. However, while you're exploring creative concepts, use whatever materials you feel best illustrate your ideas. When you get approval for your concept, improve upon the materials that inspired you. |

Then you'll want to determine the time and human resources required for the entire project or concept. What role will you play in the production? Will you need to hire outside contractors to work on the presentation (for example, character animators, programmers, and so on)? Make sure you provide ample time to produce and thoroughly test the presentation. When you've determined the time and resources necessary, you'll determine the costs involved. If this is an internal project for your company, then you won't be concerned about cost so much as the time involved — your company reps will want to know what it will cost the company to produce the piece. For large client projects, your client will probably expect a project rate — not an hourly or weekly rate. Outline a time schedule with milestone dates, at which point you'll present the client with updates on the progress of the project.

Exploring the details of the workflow process any further is beyond the scope of this book. However, there are many excellent resources for project planning. One of the best books available for learning the process of planning interactive presentations is Nicholas Iuppa's Designing Interactive Digital Media (Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998). We strongly recommend that you consult the Graphic Artists Guild Handbook of Pricing & Ethical Guidelines (Graphic Artists Guild, 2003) and the AIGA Professional Practices in Graphic Design: American Institute of Graphic Arts (Allworth Press, 1998), edited by Tad Crawford, for information on professional rates for design services.

After you have prepared your design documents for the client, it's time to have another meeting with the client or company rep. Display your visual materials (color laser prints, inkjet mockups, and so on), and walk through the charts you've produced. In some situations, you may want to prepare more than one design concept. Always reinforce how the presentation addresses the client's message and audience.

| Web Resource |

Todd Purgason's tutorial on Flash and FreeHand offers some excellent suggestions for creating high-impact presentation boards in FreeHand and tips on how to reuse graphics in print and Web projects. You can find this archived tutorial online at www.flashsupport.com/archive. |

When all is said and done, discuss the options that you've presented with the client. Gather feedback. Hopefully, the client prefers one concept (and its budget) and gives you the approval to proceed. It's important that you leave this meeting knowing one of two things:

The client has signed off on the entire project or presentation.

The client wants to see more exploration before committing to a final piece.

In either case, you shouldn't walk away not knowing how you'll proceed. If the client wants more time or more material before a commitment, negotiate the terms of your fees that are associated with further conceptual development.

When your client or company executives have signed off on a presentation concept, it's time to rock and roll! You're ready to gather your materials, assemble the crew, and meet an insane production schedule. This section provides a brief overview of the steps you need to take to produce material that's ready to go live on your Web site.

The first step is to gather (or start production of) the individual assets required for the Flash presentation. Depending on the resources you included in your functional spec and budget, you may need to hire a photographer, illustrator, animator, or music composer (or all four!) to start work on the production. Or, if you perform any of these roles, then you'll start creating rough drafts for the elements within the production. At this stage, you'll also gather highquality images from the client for their logos, proprietary material, and so on.

Of course, we're assuming that you're creating a Flash-based production. All the resources that you've gathered (or are working to create) in Phase 1 will be assembled into the Flash movie(s) for the production. For large presentations or sites, you'll likely make one master Flash movie that provides a skeleton architecture for the presentation, and use loadMovie() to bring in material for the appropriate sections of the site.

Before you begin Flash movie production, you should determine two important factors: frame size and frame rate. You don't want to change either of these settings midway through your project. Any reductions in frame size will crop elements that weren't located near the top-left portion of the Stage — you'll need to recompose most of the elements on the Stage if you used the entire Stage. Any changes in your frame rate will change the timing of any linear animation and/or sound synchronization that you've already produced.

As soon as you start to author the Flash movies, you'll create a local version of the presentation (or entire site) on your computer, or a networked drive that everyone on your team can access. The file and folder structure (including the naming conventions) will be consistent with the structure of the files and folders on the Web server. As you build each component of the site, you should begin to test the presentation with the target browsers (and Flash Player plug-in versions) for your audience.

Even if you're creating an all-Flash Web site, you need a few basic HTML documents, including:

A plug-in detection page that directs visitors without the Flash Player plug-in to the Macromedia site to download the plug-in.

HTML page(s) to display any non-Flash material in the site within the browser.

You will want to construct basic HTML documents to hold the main Flash movie as you develop the Flash architecture of the site.

Before you can make your Flash content public, you need to set up a Web server that is publicly accessible (preferably with login and password protection) so that you can test the site functionality over a non-LAN connection. This also enables your client to preview the site remotely. After quality assurance (QA) testing is complete (the next step that follows), you'll move the files from the staging server to the live Web server.

We've noticed problems with larger .swf files that weren't detected until we tested them from a staging server. Why? When you test your files locally, they're loaded instantly into the browser. When you test your files from a server — even over a fast DSL (digital subscriber line) or cable modem connection, you have to wait for the .swf files to load over slower network conditions. Especially with preloaders or loading sequences, timing glitches may be revealed during tests on the staging server that were not apparent when you tested locally.

| Tip |

You should use the Simulate Download feature of the Bandwidth Profiler in the Test Movie environment of Flash 8 to estimate how your Flash movies will load over a real Internet connection. See Chapter 21, "Publishing Flash Movies," for more discussion of this feature. |

In larger corporate environments, you'll find a team of individuals whose sole responsibility is to thoroughly test the quality of a nearly finished production (or product). If you're responsible for QA, then you should have an intimate knowledge of the process chart for the site. That way, you know how the site should function. If a feature or function fails in the production, QA reports it to the creative and/or programming teams. QA teams test the production with the same hardware and conditions as the target audience, accounting for variations in:

Computer type (Windows versus Mac)

Computer speed (top-of-the-line processing speed versus minimal supported speeds, as determined by the target audience)

Internet connection speeds (as determined by the target audience)

Flash Player plug-in versions (and any other plug-ins required by the production)

Browser application and version (as determined by the target audience)

| Web Resource |

It's worthwhile to use an online reporting tool to post bugs during QA. Many companies use the open source (freeware) tool called Mantis, a PHP/MySQL solution. You can find more information about Mantis at www.mantisbt.org/. Another popular bug reporting tool is Bugzilla (www.bugzilla.org). |

After QA has finished rugged testing of the production, pending approval by the client (or company executives), the material is ready to go live on the site.

After you've celebrated the finished production, your job isn't over yet. If you were contracted to build the site or presentation for a third party, you may be expected to maintain and address usability issues provided by follow-ups with the client and any support staff they might have. Be sure to account for periodic maintenance and updates for the project in your initial budget proposal. If you don't want to be responsible for updates, make sure you advise your clients ahead of time to avoid any potential conflicts after the production has finished.

You should have a thorough staging and testing environment for any updates you make to an all-Flash site, especially if you're changing major assets or master architecture files. Repeat the same process of staging and testing with the QA team that you employed during original production.

| Web Resource |

You can find an online archived PDF version of Eric Jordan's tutorial, "Interface Design," on the book's Web site at www.flashsupport.com/archive. This tutorial was featured in the Flash MX Bible (Wiley, 2002). |