1.2 The Dreamweaver MX 2004 Interface

Dreamweaver's windows let you add and modify elements of a Web page. Macromedia refers to most of these windows as panels, and Dreamweaver has an almost overwhelming number of them.

Many of these windows are used to assist with specific tasks, like building style sheets, and are described in the relevant chapters. But you'll frequently interact with four

main groups of windows: the document window, the Insert bar, the Property inspector,

and Panel groups.

NOTE

The look of these windows depends on what kind of computer you're using (Windows or Macintosh) and what changes you've made to the program's preference settings.

Even so, the features and functions generally work identically no matter what your situation. In this book, where the program's operation differs dramatically in one operating system or the other, special boxes and illustrations (labeled "For Macs Only" or "For Windows Only") will let you know.

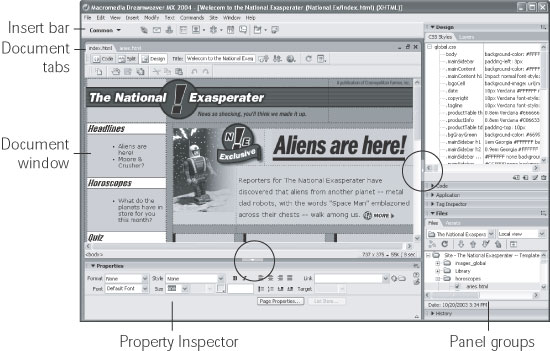

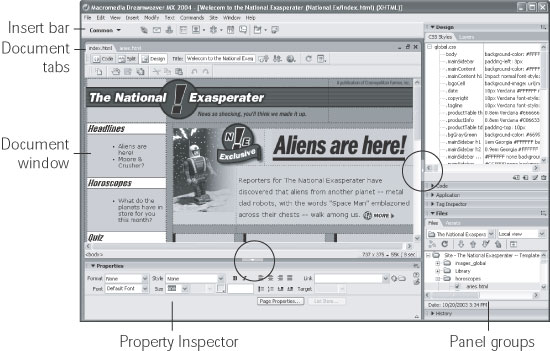

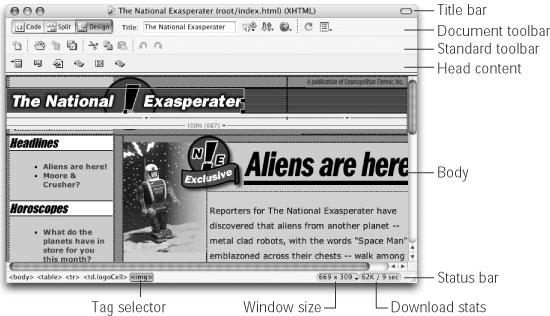

1.2.1 The Document Window

You build your Web pages in the document window. As in a word processor, you can simply click inside the document window and type to add text to the page. You'll work in this window as you build a page, and you'll open new document windows as you

add or edit pages for your site.

Several other screen components provide useful information about your document. They may appear in different locations in Windows or on the Mac (see Figures 1-1 and 1-2), but they work the same. For example:

Title bar. The title bar shows the title of the Web page you're currently working on, and, in parentheses, the name of the underlying file and what folder it's in. For instance, in the example shown in Figures 1-1, the Web page called "Welcome to the National Exasperater" is saved as an HTML file called index.html in a folder

called National Ex. (In Windows, the title bar appears on the top of the screen; on

the Mac, it's at the top of the document window.)

|

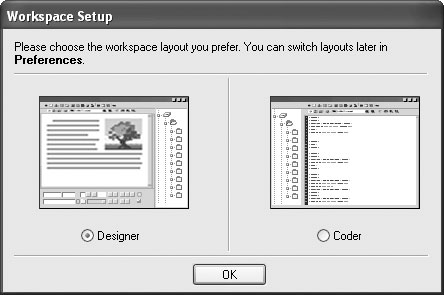

The first time you use Dreamweaver for Windows, a dialog

box asks you to select a "Workspace"梩hat is, an arrangement

of the various Dreamweaver panels and windows. You

can choose either Designer or Coder layout. (The layout

called Dreamweaver 4 is no longer

available in MX 2004.)

There's no meaningful difference

between the two: The Designer

option places the document

window on the left side of the

screen (because designers are

left-brained?), while the Coder option

places the document window

on the right. In both cases, all the

different panels and windows are fused together, filling the

screen edge to edge and top to bottom. You may be familiar

with this arrangement梜nown as the multiple document

interface (MDI)梖rom programs like Microsoft Outlook.

The Coder option is intended for users of HomeSite

(Macromedia's text-editing program), who are accustomed

to panels on the left, documents

on the right. At any time, you can

switch layouts; choose Edit Preferences, select the General

category, and then click Change

Workspace. You can then select

the layout you want from the

window pictured here. Quit and

re-open Dreamweaver to complete

the change.

Preferences, select the General

category, and then click Change

Workspace. You can then select

the layout you want from the

window pictured here. Quit and

re-open Dreamweaver to complete

the change.

For the purposes of retaining sanity (and keeping this book's

length below that price-sensitive 2,500-page barrier), this

book assumes that you're using the standard Designer

Workspace.

|

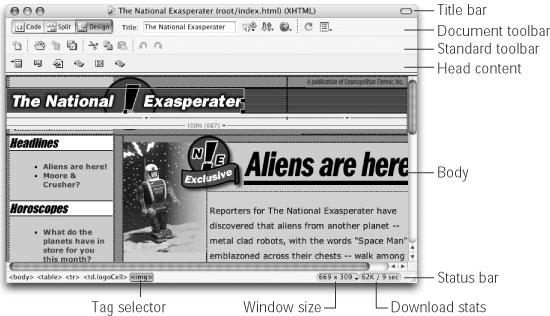

Document toolbar. The Document toolbar lets you change the title of a page, switch between Design and Code views, preview the page in different Web browsers, access a context-sensitive reference (help) system, and change the look of the document

window. You'll be reading about its various buttons and menus in the relevant

chapters of this book. (To make the toolbar visible if it's not already, choose View Toolbars

Toolbars Document.) Document.)

The Standard toolbar. The Standard toolbar includes buttons for frequent file and editing tasks like creating a new page, opening a page, saving one or all open documents, cutting, copying, pasting, and undoing and redoing actions. (This toolbar

is hidden until you summon it by choosing View Toolbars Toolbars Standard.) Standard.) Head content. Most of what you put on a Web page winds up in the body of the page, but some elements are specific to the region of the page called the head. Here you put things like the title of the page, meta tags (keywords) that provide information for some search engines and browsers, JavaScript scripts, and Cascading

Style Sheet information (Chapter 6). None of this information is actually visible on your Web page once it's "live" on the

Internet. But while working in Dreamweaver, you can have a look at it by choosing

View Head Content. You'll see a row of icons representing the different bits of

information in the head. Head Content. You'll see a row of icons representing the different bits of

information in the head.

|

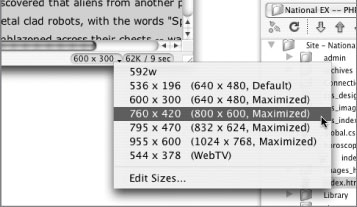

Creating pages that look good on different monitors set to

a wide range of resolutions is one of the most difficult tasks

facing Web designers. After all, not everyone has a 21-inch

monitor or views Web sites with the browser window maximized

to fill the whole screen. Nothing is more dispiriting

than spending a solid week designing the coolest looking

Web page, only to have your client call up to say that your

design doesn't fit his 15-inch

monitor (a painfully common

story).

You can simulate browser

windows of different sizes by

dragging the resize handle at

the lower-right corner of the

document window, of course.

But Dreamweaver has a better

tool for such experiments:

the Window Size Pop-Up

Menu on the status bar at the bottom of your document

window. Clicking the black arrow next to the window-size

stats lets you choose a different setting for the document

window, as shown here. Use this feature to test how your

page will look inside different-size browser windows. The

numbers indicate the width and height in pixels.

(Windows note: If your document window is maximized,,

this feature doesn't work. Choose Window Cascade to "unlock" the document window from its space on the screen.

Now you're free to resize the window and use the Window

Size Pop-Up Menu.) Cascade to "unlock" the document window from its space on the screen.

Now you're free to resize the window and use the Window

Size Pop-Up Menu.)

The first pair of numbers indicates the amount of usable

space in the document window; the numbers in parentheses

indicate the resolution of the monitor. The fourth option

shown here, in other words, indicates that if someone

has a 800 x 600 monitor

and maximizes the browser

window, there are 760 by

420 pixels of space to display

a Web page. (Even though a

monitor's resolution is, say,

800 x 600, after you subtract

the space required to display

the browser's toolbar, location

bar, status bar, and other

"chrome," 760 x 420 pixels of

space will be visible when a Web page is opened.)

In any case, note that the window size pop-up menu doesn't

actually set the size of your Web page or add any code to

your page; Web pages are usually fluid, and can grow or

shrink to the size of each visitor's browser window. For

techniques that let you exercise greater control of your page

presentation, see Chapter 7.

|

The status bar provides useful information about your page. It appears at the bottom of the document. The tag selector (shown in Figure 1-2) is also extremely useful. It provides a sneak peek at the HTML codes that, behind the scenes, compose your Web page. It indicates how tags are nested in the document, based on what you've selected or where

the insertion point is. You can also use the tag selector to select an HTML tag and

all of the information nested inside it. For instance, clicking the <p> selects the

paragraph and everything inside it. This feature is very useful when you want to

set properties (see the Property inspector below), add Behaviors (Chapter 12), or

precisely control the application of styles (Chapter 6). You'll make good use of the tag selector in the tutorials to come. For experienced

Dreamweaver fans, it's one of the program's most popular tools.

|

In Design View, clicking the <body> tag in the tag selector is the same as pressing Ctrl+A ( -A): it selects everything in the document window. After selecting everything this way, for example, you could press the Delete key to instantly get rid of everything in your document. -A): it selects everything in the document window. After selecting everything this way, for example, you could press the Delete key to instantly get rid of everything in your document.

Careful, though. The same operation in Code view selects all of the code. Deleting this gives you an empty file梐nd an invalid Web page.

|

|

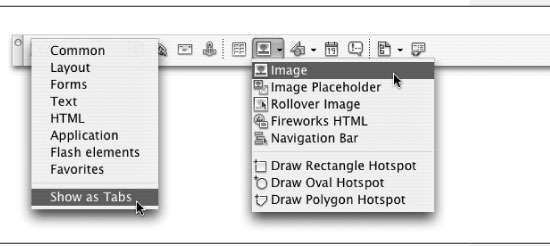

1.2.2 The Insert Bar

If the document window is your canvas, the Insert bar holds your brushes and paints, as shown in Figure 1-3. While you can add text to a Web page simply by typing in the document window, adding elements like images, horizontal rules, forms, and multimedia

elements is simplified by the click-to-add approach of the Insert bar. Want to

put a picture on your Web page? Just click the Image icon.

NOTE

Adding elements to your Web page this way may feel like magic, but the Insert bar is really just a

quick way to add code to a page, whether it's HTML, XHTML, JavaScript, or server-side code like Visual Basic

(see Part VI of this book). Clicking the horizontal rule icon, for instance, simply inserts the <hr> tag into the

underlying HTML of your page. Of course, Dreamweaver's visual approach hides that messy code, and

cheerfully displays a gray horizontal bar on the page.

When you first start Dreamweaver, the Insert bar is open (see Figure 1-3). If you ever close it by mistake, you can open it again by choosing Window Insert or by pressing Ctrl+F2 ( Insert or by pressing Ctrl+F2 ( -F2). On the other hand, if space is at a premium on your screen, you can close the Insert bar and use the Insert menu instead. Its commands duplicate all

of the objects available from the Insert bar. -F2). On the other hand, if space is at a premium on your screen, you can close the Insert bar and use the Insert menu instead. Its commands duplicate all

of the objects available from the Insert bar.

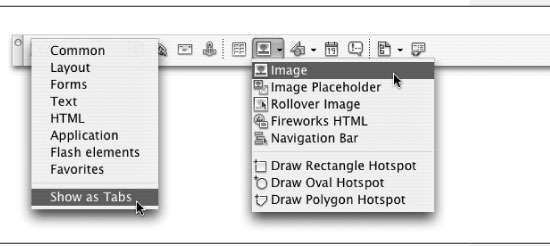

Eight different sets of objects are available from the Insert bar, each available from the pop-up menu at the left end (see Figure 1-3). Select a category from the menu to see the corresponding category of objects worth inserting:

Common objects. In addition to images, tables, and horizontal rules, which you'll use frequently in everyday Web design, this category of the Insert bar offers access to Dreamweaver's Template features. Templates let you build basic Web page designs that you can use over and over again in your site, speeding up your production

process and facilitating easy updates. See Chapter 18 for details. Layout objects. The objects in this category help you control the layout of a Web page by organizing a page's contents using HTML tables or layers. In addition, this

panel lets you use Dreamweaver's Layout view梐 customized approach to building

complex table designs that's covered in Chapter 7.

Form objects. Want to get some input from visitors to your Web site? You can use forms to receive their comments, collect credit card information for online sales, or gather any other kind of data. The Forms tab lets you add form elements like

radio buttons, pull-down menus, and text boxes (see Chapter 11). You'll also use this tab when building the dynamic Web pages discussed in Part VI. Text objects. For formatting type, making it bold or italic, for instance, you can turn to the Text category. Most of the buttons on this tab aren't technically objects; they

don't insert new objects onto the page. Instead, they format text already present

on the page. For the most part, the Property inspector offers the same formatting

options and is a more common tool for formatting text.

|

Using the Text objects tab can be disorienting. Some "text objects" create incomplete HTML and actually dump you into the raw HTML of the page, leaving the nice visual Design view behind. In general, the Property inspector and Text menu let you do everything in this tab梞ore quickly and more safely.

|

|

HTML objects. This grab bag inserts elements that appear only in the <head> of a document (like keywords used for search engines), tags used for building tables

and frames and objects to insert JavaScript code, and horizontal rules. Like text

objects (above), some of these work only in Code view. Application objects. Dreamweaver makes connecting your Web pages to databases as easy as clicking a few buttons. (OK, almost as easy; see Part VI.) The Application

tab adds many powerful tools for building dynamic pages: controls that add records

to your database, for example, or that update information already in a database. Flash elements. Although nearly empty, this category (new in Dreamweaver MX 2004) is intended to hold future Flash elements桭lash movies that you can customize with Dreamweaver. At this writing, only one object shows up here桰mage

Viewer, which lets you build Flash slideshows (Section 13.2). Favorites. Perhaps the most useful category, Favorites can be anything you want

it to be. That is, after you've discovered which objects you use the most (like the

Image command, if you work with a lot of graphics), you can add them to this

personal category. You may find that once you've customized this tab, you'll never

again need the other categories in the Insert bar. For instructions on adding objects

to your Favorites tab, see the box in Section 4.3. ASP, PHP, JSP, .NET, Cold Fusion. If you're building database-driven Web pages,

you'll discover yet another category of objects. The exact name of the category

depends on the server model you're using (Microsoft's Active Server Page, or

Macromedia's Cold Fusion server, for example), but it always contains frequently

used code snippets for that programming language. See Chapters 21 through 24 for more on working with databases.

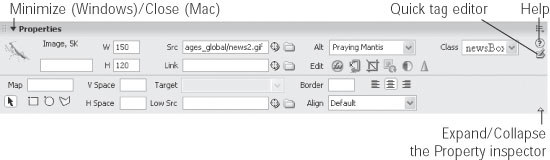

1.2.3 The Property Inspector

After dropping in an image, table, or anything else from the Insert bar, you can use

the Property inspector to fine-tune its appearance and attributes. Suppose, for example,

that your boss has decided he wants his picture centered in the middle of the

page. After highlighting his picture in the document window, you would then use the

Property inspector to change its alignment.

The Property inspector (Figure 1-4) is a chameleon. It's aware of what you're working on in the document window梐 table, an image, some text梐nd displays the appropriate set of properties (that is, options). You'll use the Property inspector

extensively in Dreamweaver.

For now, though, here are two essential tips to get you started:

Double-click any blank gray area in the Property inspector梠r striped area in Mac OS X梩o hide or show the bottom half of the palette, where Dreamweaver displays

an additional set of advanced options. (It's a good idea to leave the inspector fully

expanded most of the time, since you may otherwise miss some useful options.)

At its heart, the Property inspector is simply a display of the attributes of HTML

tags. The src (source) attribute of the <img> (image) tag, for instance, tells a Web

browser where to look for an image file. The best way to make sure you're setting the properties of the correct object is to

click its tag in the tag selector (see Section 1.2.2).

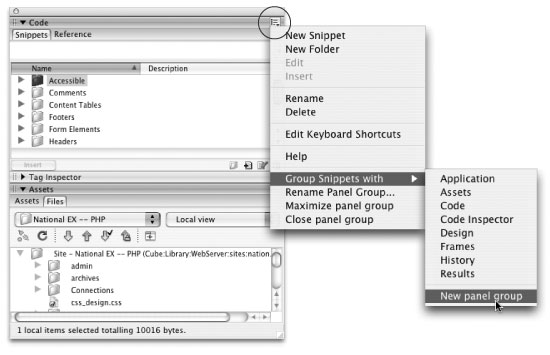

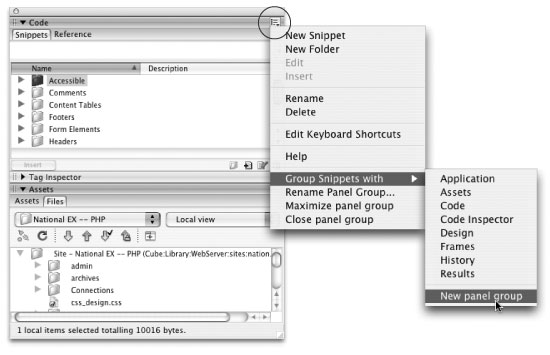

1.2.4 Panel Groups

So far, this chapter has described the Insert bar, Property inspector, and document

window梑ut those are just the beginning of Dreamweaver's windows. In Dreamweaver

MX 2004, most of the remaining windows梒alled panels梥it in tidy groups

on the right edge of your screen.

For example, a panel group named Code harbors panels for working with Snippets

and viewing Web References (see Figure 1-5).

|

To view the panels in a group, click the expander arrow or the panel group's name; to hide the panels, click the arrow (or name) again.

|

|

The various panels and their uses will come up in relevant sections of this book. But

a few tips concerning Dreamweaver's panels are worth noting here:

Double-click anywhere in a panel group's gray title bar to open that panel group and expand it to fill the maximum space available. This is really the best way to open a panel group. Not only is the title bar a larger target, but most panels contain a lot of information. You'll want to see as much

of it as possible. You can even rename a panel group. Maybe the name Code doesn't make sense as the name of a panel group; after all, there are plenty of different kinds of codes

involved in building Web sites. To rename a group, open its contextual menu, either by clicking the menu icon (see Figure 1-5) or by right-clicking (Windows) or Control-clicking (Mac) the title bar.

In the contextual menu, choose Rename Panel Group. Type the new name in the

resulting window?span class="docEmphasis">HTML, in this example梐nd then click OK. If you want to hide all windows except for documents, choose Window Hide Panels or press F4梐 useful trick when you want to maximize the amount of your screen dedicated to showing the actual Web page you're working on. To bring back

all of Dreamweaver's administrative windows, press F4 again or choose Window Hide Panels or press F4梐 useful trick when you want to maximize the amount of your screen dedicated to showing the actual Web page you're working on. To bring back

all of Dreamweaver's administrative windows, press F4 again or choose Window Show Panels.

Show Panels.

|

Dreamweaver for Windows includes a button for hiding only the panel groups. See Figure 1-1 for this handy trick.

|

|

If you've really made a mess of your screen by dragging Dreamweaver windows all over the place, you can make them snap back into a tidy arrangement by choosing

Window Arrange Panels. (Unfortunately, this command arranges only tool

panels and inspector windows. It doesn't arrange your document windows or, on

the Mac, the Site window.) Arrange Panels. (Unfortunately, this command arranges only tool

panels and inspector windows. It doesn't arrange your document windows or, on

the Mac, the Site window.)

|

Hide Panels or press F4梐 useful trick when you want to maximize the amount of your screen dedicated to showing the actual Web page you're working on. To bring back

all of Dreamweaver's administrative windows, press F4 again or choose Window

Show Panels.

Arrange Panels. (Unfortunately, this command arranges only tool

panels and inspector windows. It doesn't arrange your document windows or, on

the Mac, the Site window.)